Is Human Intelligence Simple? Part 1: Evolution and Archaeology

How did we get so smart?

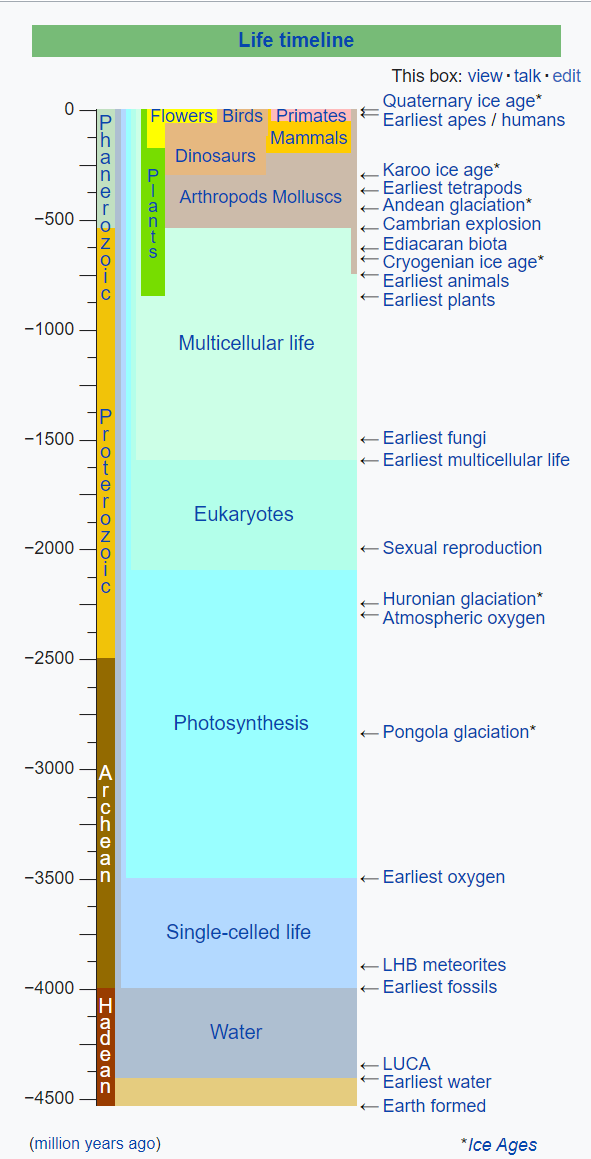

If you zoom way out and look at the history of life on Earth, humans evolved incredibly recently. The Hominidae — the family that includes orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and humans — only arose 20 million years ago, in the most recent 0.5% of evolutionary history.

Within the Hominidae, in turn, Homo sapiens is a very recent development:

We appeared 800,000-300,000 years ago, or in the last 1.5%-5.3% of hominid history.

If you look at early hominid “technological” milestones like tool use or cooking, though, they’re a lot more spread out over time. That’s interesting.

There’s nothing to suggest that a single physical change in brains should have given us both tool use and fire, for instance; if that were the case, you’d expect to see them show up at the same time.

Purposeful problem-solving behaviors like tool use and cooking are not unique to hominids; some other mammals and birds use tools, and lots of vertebrates (including birds and fish) can learn to solve puzzles to get a food reward. The general class of “problem-solving behavior" that we see, to one degree or another, in many vertebrates, doesn’t seem to have arisen surprisingly fast compared to the existence of animals in general.

However, to the extent that Homo sapiens has unique cognitive abilities, those did show up surprisingly recently, and it makes sense to privilege the hypothesis that they have a common physical cause.

So what are these special human-unique cognitive abilities?

In archaeology there’s a concept of behaviorally modern humans, a suite of behaviors that all arise after the earliest evidence of anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

The new behaviors include1:

art and ornaments

bone, ivory, and shell artifacts such as needles and pins

evidence of ritual in the form of elaborate graves

elaborate hearths, oldest “ruins”

transport of desirable rock materials over hundreds of kilometers

fishing

rapid increase in human population density, geographic range, and artifact diversity

There is some dispute about when these behaviors actually began. In the 90s, it was thought that they only dated back to 50,000-40,000 years ago. However, older and older archaelogical evidence keeps getting discovered; now the oldest evidence of anatomically modern Homo sapiens is more like 195,000-160,000 years ago, while a new archaeological site at Pinnacle Point in South Africa shows evidence of decorative ochre use, fishing, and bladelet technology 164,000 years ago.2

But even with the dates of the earliest “modern” behaviors being pushed back, it still looks like “behaviorally modern humans” arose after hominid brains had reached their current size.

This is consistent with two hypotheses:

Some other change in Homo sapiens or its environment, besides larger brains, led to all these cultural innovations. OR,

When brains reached a certain size, there was some kind of “phase change” that made lots of new skills show up all at once.

What clearly didn’t happen was a gradual acquisition of the “behaviorally modern” repertoire across the long evolutionary period when brains were getting bigger.

One piece of evidence that suggests that modern behavior wasn’t a single point of genetic divergence is that Neanderthals seem to have also made ornaments.3 Pierced and pigmented scallop shells as body ornaments have been found in Neanderthal settlements in Spain, dating to 50,000 years ago.

The alternative hypothesis put forward is that “cultural” activities like ornaments or rituals appear in high-population-density groups of relatively-advanced hominids, whether Homo sapiens or Homo neanderthalensis. Living in groups creates a need for culturally sophisticated behavior, and both species are physically capable of producing that behavior, so they do.

Another piece of evidence against a single point of genetic divergence is that Homo sapiens brains did gradually change over the past few hundred thousand years — not in overall size, but in shape. Older Homo sapiens skulls are shaped more like Homo erectus skulls than contemporary human skulls are.4

A multivariate regression of endocranial shape on geologic age explains 21.9% of shape variance (P < 0.01) and corresponds to a change from an elongated to a globular shape: From geologically older to younger H. sapiens, the frontal area becomes taller, the parietal areas bulge, the side walls become parallel, and the occipital area becomes rounder and less overhanging. Moreover, the cerebellum becomes relatively larger and more bulging, the cranial base more flexed, and the temporal poles narrower and oriented anterior-medially.

But even if there was a gradual change in Homo sapiens skull morphology and even if “behaviorally modern” repertoires are shared with other species like Neanderthals, it still doesn’t refute the fact that there was more “technological progress” in the last hundred thousand years of hominid prehistory than in the preceding several million.

Possibly there’s some kind of compounding effect, where having complex/advanced skills means humans are more able to acquire further, even more complex/advanced skills. You could imagine this happening either at a cultural level (inventions enable further inventions) or at a genetic level (the rise of a new behavioral trait creates some environmental condition like higher population density, which causes stronger selection for more human-like behavioral adaptations.)

If there’s something like an “attractor basin” in evolutionary/cultural history for human intelligence, that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a simple mechanism for human intelligence on the neurological or computational level.

If humans “got smart” through some kind of feedback loop where sophisticated behaviors drove greater evolutionary or cultural selection for ever more sophisticated behaviors, then we can’t necessarily analogize human intelligence development to artificial intelligence development at all, since computer programs don’t have lifespans or reproduction in the same way as organisms.

The evolution and prehistory of Homo sapiens and its ancestors seems to weakly point against the “single discrete origin point for human intelligence” hypothesis.

some kinds of “practical problem-solving intelligence”, like basic tool use, appear to have been developed slowly and gradually, and predate our species.

being Homo sapiens is neither necessary nor sufficient for the cluster of sophisticated behaviors known as “behavioral modernity.”

Hominid evolutionary selection for bigger brains was gradual, over hundreds of thousands of years; Homo sapiens selection for rounder skulls and flatter faces is also a gradual process that has continued even into “recent” times (between the Stone Age and today).

The development of all human history, technology, and culture is, of course, a blink of an eye in evolutionary time. There’s definitely such a thing as acceleration in behavioral sophistication. Hominids made stone tools in pretty much the same way for more than a million years before “suddenly” advancing to new techniques around 200,000-50,000 years ago (depending on which archaeologist you ask.)

But, so far, I’m not seeing a clear smoking gun for a discrete genetic change or handful of changes that enabled this “explosion” of culture, which would prompt us to go looking in the brain for a physiological “key” to human intelligence.

I’m going to wait for the next post to look at the evidence from paleogenetics, the surprisingly new (<20 years!) body of evidence derived from genetic sequencing of ancient bones.

How did hominid and human genes change, and do any of those changes give clues to the origin of human intelligence? Stay tuned!!

Klein, Richard G. "Anatomy, behavior, and modern human origins." Journal of world prehistory 9.2 (1995): 167-198.

Nowell, April. "Defining behavioral modernity in the context of Neandertal and anatomically modern human populations." Annual review of anthropology 39.1 (2010): 437-452.

Zilhão, João, et al. "Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neandertals." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107.3 (2010): 1023-1028.

Neubauer, Simon, Jean-Jacques Hublin, and Philipp Gunz. "The evolution of modern human brain shape." Science advances 4.1 (2018): eaao5961.

I had trouble parsing part of this, so let me rewrite it in my own words:

There used to be a question of why there was 100ky of "anatomically modern humans" before there were "behaviorally modern humans." Recently, the evidence of behavioral modernity has been pushed back, so there no longer is a gap in time between anatomical modernity and behavioral modernity. But this gap was only the tip of the iceberg. It was a tidy way of talking about the mystery, but removing it doesn't remove the actual mystery; comparing anatomical modernity and behavioral modernity is a category error, because anatomical modernity is an endpoint, whereas behavioral modernity is a starting point. The brains got larger for millions of years, leveling off 150kyo, and then behavioral change accelerated, lots of new behavior starting then. But if the big brains lead to the modern behavior, why didn't the behavior accumulate for millions of years? This is the real mystery and moving modern behavior back 100k more years doesn't help address it.

I'm surprised that you have not even mentioned language, something which took evolution of the jaw, tongue, throat as well as brain and which would have revolutionized hominid culture. Have you read Julian Jaynes "The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind". I don't know if I believe Jaynes, but he made the importance of language clear to me.