Who Wants Stricter Rules?

In my last post, I explained that a community with shared values can establish its own code of law and court system, and that such systems can be incentive-compatible and robustly maintain community norms.

These kinds of sustainable community self-governance can work even when the community has no “state” of its own and is subject to the jurisdiction of another state.

The limits on self-governance are clear: a community cannot do things that the state de facto forbids. The state employs men with guns who will try to stop you from doing certain things; organizing with some like-minded people into a “community” does not change this fact.

So, a community based around a private code has to distinguish itself from the surrounding culture by being stricter, not looser, than the range of what’s de facto permitted outside the community.

When might you want this? Who might voluntarily want to bind themselves to stricter rules than they have to?

The obvious first example is religious communities.

Most of my historical examples of non-state legal systems that existed alongside states are examples of religious communities. The Amish, the Quakers, the Diaspora Jews, and so on, have rules of religious observance not shared by the surrounding population, and have accordingly developed institutions to preserve those norms. The Roma have cultural (not quite religious, I think) rules of ritual purity that similarly are not shared by the surrounding nations.

In an increasingly secular environment, it’s easy to see why religious traditionalists would try to make “their own” communities and institutions that support their values when the surrounding world does not. This rhymes, for instance, with Rod Dreher’s call for “The Benedict Option”, the creation of independent traditionalist Christian communities and institutions.

But what about the rest of us?

What kinds of secular people would want to communally and enforceably commit to a set of stricter rules than the surrounding environment demands?

The Network State gives only one example — “Keto Kosher”, a community based around maintaining and supporting a set of strict dietary and lifestyle norms (in this case, the controversial “keto diet”), justified on the basis of health rather than religious ritual.

This is a decent example, but not a great one.

Yes, it’s easier to follow a diet or exercise program if you have social accountability and helpful physical infrastructure (like a walkable city). The benefits of community membership are concrete, and so the threat of expulsion from the community is a real incentive. And some people care a lot about their health and fitness…potentially enough to let health considerations drive important personal decisions like where they live or how they make a living.

I doubt anyone would risk their life for a healthy diet, though; it’s hard to see how the Keto Enclave could inspire the kinds of acts of courage and loyalty that you see in the history of actual new nations winning their independence.

I propose an alternative application for community self-governance: professional ethics.

Courts for Professional Ethics

Don’t laugh; I’m serious.

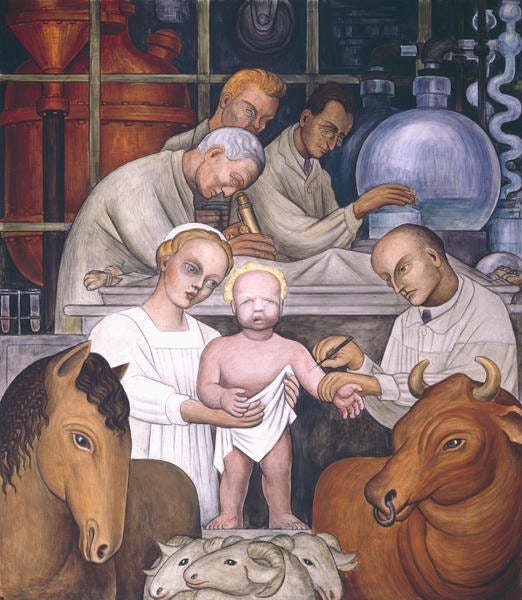

Professions are examples of communities that, at least ideally, hold themselves to a higher standard than ordinary people.

A doctor is supposed to live by a code — to do no harm and heal the sick, no matter what. “You set the leg.”

A journalist is not supposed to reveal the identity of an anonymous source.

A scientist is supposed to follow unusually careful standards of intellectual integrity.

Membership in a learned profession is supposed to be a position of unusual trust, earned through unusual trustworthiness. It is not ordinarily a safe proposition to let someone take a knife to your body; but you might let a surgeon do it.

We obviously live in a time when the general public’s trust in professional institutions is collapsing. The professions are seen as serving the interests of a privileged class with its own ideology; and real examples of institutional dysfunction and outright fraud are abundant. In fact, 2% of scientists admit to fabricating data, and 14% admit to personally knowing a colleague who did so.

But, I think, many people aren’t wholly cynical about professional ethics, even now. Professionals are emotionally invested in being good at their jobs.1 Professionals are socialized from a fairly young age in the ideals of their professions — what it means to be a good lawyer, a good engineer, a good scientist, etc — and even though they may be demoralized by the abandonment of those ideals, they still often retain the memory of caring about them sincerely.

People — especially educated professionals — spend a huge amount of their lives at work or in school. When professionals feel like their days are spent on fake things, or that they suffer from “impostor syndrome”, or that their profession is actually more ignoble than they once believed, there’s a tremendous amount of emotional “potential energy” tied up in that disappointment. That energy could be liberated into motivation if people had some hope of a better way. A renewal, or rededication, of the profession to the kinds of ideals it once upheld, but this time on a firmer foundation equipped to deal with the challenges of the present world. I think even some people who consider themselves hardened cynics would weep with joy if they thought they had a chance of rekindling that light.

And, of course, non-professionals need some way to determine whom to trust. “Trust nobody” doesn’t work. Neither do increasingly shrill and censorious commands to “trust the experts.” There needs to be some way that a stranger can earn your trust; otherwise we have to go back to a kind of clannish barbarism where only family can be trusted. We know what that looks like; it’s most of human history, and it’s most of the developing world today, and it’s not great!

How could membership in a profession become a badge of trustworthiness, a hard-to-fake signal of integrity?

Obviously, the profession would have to have an enforcement mechanism for its professional ethics. You’d have to credibly demonstrate that professionals who break the “code” will (perhaps after an initial warning) be kicked out.

For state-licensed professions like doctors and lawyers, of course there is a complex body of law around what kinds of misconduct can result in losing one’s license to practice.

But there is not, as far as I know, a private governance system in which (for instance) researchers who violate the public’s trust are formally and publicly investigated and could lose a “badge” of professional membership.

Research misconduct is not, in itself, illegal. (There are regulations against research misconduct for those who receive grant support from the US Government, for instance here. Also, research fraud by recipients of federal grant money can be prosecutable under the False Claims Act.)

Researchers can be fired from their institutions for misconduct, of course, but a university’s internal deliberations are opaque to the public, and its firing decisions are relatively discretionary. Discretionary opaque judgments don’t generate trust if it isn’t already there.

What you need is some kind of a formal public investigation, with arguments on both sides, about whether someone committed research fraud.

Or, a formal public investigation, with arguments on both sides, about whether they knowingly made false or misleading statements to the press or to government officials or to the general public.

How It Works: The Basics

Here’s how a “professional association with teeth” might work, for the specific example of investigating research misconduct.

A professional association maintains a publicly visible list of members.

The professional association publicly shares a protocol for how to conduct research misconduct investigations. Anyone who follows the protocol can set up a “science court” of their own.

The professional association removes a person from the membership list if they refuse to cooperate with a valid (= protocol-conformant) investigation.

The professional association also associates each member with a public record of their history of investigations, including whether they were “cleared” or “convicted” of misconduct.

Optionally, some categories of research misconduct can also carry a penalty of expulsion from the professional association.

Note that this is a decentralized court system. Outsiders can investigate insiders. 2

You want something that a motivated outsider can audit. A layman can see someone’s name, and check if he’s a member of the professional association, and read the records of any investigations and their results.

Now, how should the investigation itself work?

The best inspiration for court procedures, of course, should come from actually-existing court procedures, in the Anglo-American common law tradition. These procedures will need to be modified to be simpler, to make use of today’s technology, and to account for the fact that the court will be administered by private citizens rather than the state.

Some essential desiderata, though, are:

There must be definitions of research misconduct, written and shared publicly.

Transcripts of investigations must be made public.

Both the plaintiff and defendant must be allowed to make arguments. The accused has a right to argue in their own defense.

The verdict must be decided by a panel of jurors who must not be members of the accused’s profession, and ideally must not even be members of the same social class or extended community.

one possible selection criterion: “no college degree allowed” + “must pass a standardized test on logic problems and reading comprehension”

“Science Courts” and “Fact Forums”

In his book “Engines of Creation”, written in 1986, Eric Drexler laments the lack of a trustworthy, widely accepted way for our society to evaluate the safety and benefits of new technology.

Government and industry - and their critics - commonly appoint expert committees that meet in secret, if they meet at all. These committees claim credibility based on who they are, not on how they work. Opposed groups recruit opposed Nobel laureates.

To gain influence in our mass democracy, groups try to outshout one another. When their views have corporate appeal, they take them to the public through advertising campaigns. When their views have pork-barrel appeal, they take them to legislatures through lobbying. When their views have dramatic appeal, they take them to the public through media campaigns. Groups promote their pet experts, the battle goes public, and quiet scientists and engineers are drowned in the clamor.

As the public conflict grows, people come to doubt expert pronouncements. They judge statements the obvious way, by their source. ("Of course she claims oil spills are harmless - she works for Exxon." "Of course he says Exxon lies - he works for Nader.")

When established experts lose credibility, demagogues can join the battle on an equal footing. Reporters - eager for controversy, striving for fairness, and seldom guided by technical backgrounds-carry all sides straight to the public. Cautious statements by scrupulous scientists make little impression; other scientists see no choice but to adopt the demagogues' style. Debates become sharp and angry, divisions grow, and the smoke of battle obscures the facts. Paralysis or folly often follows.

Of course, the problem is even worse today.

But Drexler thought it was solvable!

He proposes a court-like institution called a “fact forum.” This is a deliberative body for investigating questions of fact (rather than allegations of wrongdoing).

We need better procedures for debating technical facts - procedures that are open, credible, and focused on finding the facts we need to formulate sound policies. We can begin by copying aspects of other due-process procedures; we then can modify and refine them in light of experience. Using modern communications and transportation, we can develop a focused, streamlined, journal-like process to speed public debate on crucial facts; this seems half the job. The other half requires distilling the results of the debate into a balanced picture of our state of knowledge (and by the same token, of our state of ignorance). Here, procedures somewhat like those of courts seem useful.

Since the procedure (a fact forum) is intended to summarize facts, each side will begin by stating what it sees as the key facts and listing them in order of importance. Discussion will begin with the statements that head each side's list. Through rounds of argument, cross examination, and negotiation the referee will seek agreed-upon statements. Where disagreements remain, a technical panel will then write opinions, outlining what seems to be known and what still seems uncertain. The output of the fact forum will include background arguments, statements of agreement, and the panel's opinions. It might resemble a set of journal articles capped by a concise review article - one limited to factual statements, free of recommendations for policy.

The “fact forum” would be:

judged by a panel of technically educated jurors

both parties in the dispute must agree on who the jurors are

allow advocates for both sides to present their case, according to technical rules for argumentation analogous to the rules of evidence in a trial

Drexler argued that these “fact forums” could be administered by the government, but might be even better if they were implemented privately:

Governments may yet act to establish science courts, and any steps they may take toward due process merit support. Yet it is reasonable to fear government sponsorship of science courts: centralized power tends to beget lumbering monsters. A central "Science Court Agency" might work well, do little visible harm, and yet impose a great hidden cost: its very existence (and the lack of competition) might block evolutionary improvements.

Other paths lie open. Fact forums will he able to exert influence without help from special legal powers. To have a powerful effect, their results only need to be more credible than the assertions of any particular person, committee, corporation, or interest group. A well-run fact forum will carry credibility in its very structure. Such forums could be sponsored by universities.

In fact, Dr. Kantrowitz recently conducted an experimental procedure at the University of California at Berkeley. It centered around public disputes between geneticist Beverly Paigen and biochemist William Havender regarding birth defects and genetic hazards at the Love Canal chemical dump site. They served as advocates; graduate students served as a technical panel. The procedure involved meetings spread over several weeks, chiefly spent in discussing areas of agreement and disagreement; it wound up with several sessions of public cross-examination before the panel. Both the advocates and the panel agreed to eleven statements of fact, and they clarified their remaining disagreements and uncertainties.

Arthur Kantrowitz and Roger Masters note that "in contrast to the difficulties experienced in the many attempts to implement a science court under government auspices, encouraging results were obtained in the first serious attempt... in a university setting." They remark that the traditions and resources of universities make them natural settings for such efforts. They plan more such experiments.

This shows a decentralized way to develop due-process institutions, one that will let us outflank existing bureaucracies and entrenched interests. In doing this, we can build on established principles and test variations in the best evolutionary tradition.

Drexler credits physicist Arthur Kantrowitz with the original idea.

Dr. Kantrowitz's concern with due process arose out of the U.S. decision to build giant rockets to reach the Moon in one great leap; he, backed by the findings of an expert committee, had recommended that NASA use several smaller rockets to carry components into a low orbit, then plug them together to build a vehicle to reach the Moon. This approach promised to save billions of dollars and develop useful space-construction capabilities as well. No one answered his arguments, yet he failed to win his case. Minds were set, politicians were committed, the report was locked in a White House safe, and the debate was closed. The technical facts were quietly suppressed in the interests of those who wanted to build a new generation of giant rockets.

Kantrowitz’s original 1979 article, “Democratic Control of Technology”, focused on the problem of scientific advice to politicians becoming politicized.

For example, Kantrowitz points out, the President’s Science Officer will never be an independent or unbiased advisor. “It is clear that an appointed special assistant to the President must share the politics and the values systems of his client in order to retain influence.”

In fact, all science that receives federal funding has compromised incentives — scientists are unlikely to criticize the same government on whose support they depend.

Since World War II US science has increasingly depended on financial support from the Federal Government. Scientists in Washington have two roles: first, they provide advice, frequently on a confidential basis, to politicians, and econd, they appeal for funding for science. It has become painfully clear that this conflict of interest weakens the influence of the scientific establishment in providing scientific information needed for the making of public policy.

“Insider” scientists are corrupted by their incentives to appeal to the government for grants and influence; but Kantrowitz also mistrusts “outsider” scientists, such as Rachel Carson, who appeal directly to the public with advocacy against such technologies as pesticides or nuclear power. These “outsiders” can easily become mere demagogues who get their way by appealing to the emotions of the ignorant.

Kantrowitz thought that scientific and technological progress itself was in danger, so long as all public discourse about science and technology was conducted by such obviously biased and unprincipled processes.

Out of this confusion has come the resurrection of the ancient doctrine that mankind cannot summon up the wisdom necessary to control the enormous power created by science based technology. The power of this reaction stands today as an historic challenge to the future of the whole magnificent enterprise embodied in the idea of progress.

In place of progress, the notions of mankind's limitations as set forth by Malthus' reaction to this idea have again become dominant political doctrine. We are today witnessing an almost deafening crescendo that high technology is evil, that small is beautiful, and that we must return to an earlier more primitive state

…

The reactionary movement against science based technology has presently so decelerated progress, and even more dimmed our view of the opportunities that technological progress can create for our future, that the Malthusian neglect of creativity again appear plausible. Neglecting creativity we can, of course, easily arrive at the array of deadly problems which the Club of Rome calls the problematique, that we will not be able to find the resource that are the raw material for industrialized society, that we will not be able to dispose of its polluting waste products. The power of this reaction in the United States has produced a situation that can be described as paralyzed anxiety.

Kantrowitz is particularly troubled by the decline of nuclear power and the increase in “burdensome regulation” on new technologies in healthcare — two trends which certainly have progressed since the time of his writing! He continues,

It is the clear responsibility of the scientific community to communicate the factual basis for decision making in a credible way. It is to this responsibility that this paper is addressed.

There is a medical condition known as anxiety neurosis in which a patient is obsessed with uncertainties to such a degree that he is unable to act rationally. It is interesting to note that a therapy found most useful in this situation is the introduction of a calm person. Perhaps it is the mission of the scientific community to introduce the much needed calm that could help the United States recover from paralyzed anxiety.

The solution Kantrowitz proposes is the Science Court.

A Science Court Administration, once assigned by a governmental agency to investigate a controversial scientific issue relevant to public policy, would assign a Case Manager (CM) to each side of the issue.

Kantorowitz suggests a possible procedure for Science Court:

The CMs formulate a series of factual statements which they regard as most important to their cases. Such statements must be results, or anticipated results, of experiments or observations of nature. The statements should be ranked in order of importance assigned by the CM.

The judges examine each statement to determine that it is relevant and factual.

The CMs then exchange statements. Each side is invited to accept or challenge each of the opponent's statements.

The list of statements accepted by both sides will constitute the first output from the Science Court.

Challenged statements are first dealt with by a mediation procedure in which attempts are made to narrow the area of disagreement or to negotiate a revised statement of fact which both CMs can accept.

The mediated statements are added to the Science Court's output. Those statements which remain challenged are then subjected to an adversary procedure.

CMs prepare substantiation papers on statements remaining challenged and transmit these to the judges and the opposing CMs, starting with the first, the most important challenged statement.

The substantiation is cross-examined by opposing CM and judges and contrary evidence is presented and cross-examined.

A second attempt to negotiate a mediated statement is made and, if successful, this statement is added to the Science Court's output.

If this is not successful the judges write their opinions on the contested statement of fact.

This procedure is repeated for each of the challenged statements.

The accepted statements plus the judges' statements constitute the' final output of the procedure.

This procedure basically amounts to a structured debate.

Why should a structured debate by scientifically educated people do any good? What if policymakers don’t want to listen to the Science Court?

Well, of course, they don’t have to, and in fact they didn’t. The Science Court was never formally established, despite three presidents endorsing the idea.

Having a structured, two-sided, fact-based, public debate between experts on a controversy doesn’t ensure that disagreements will be resolved, or that the results of the debate will be unbiased, or that anyone will care. But it is certainly better than not even attempting to have such a debate.

Why?

An investigatory body doesn’t have to be perfect, and doesn’t have to start out with any kind of power; it can gain influence if it is conspicuously the highest-quality and most impartial institution around.

If a single, well-known, conspicuously high-quality Science Court exists, it establishes common knowledge among people who do value inquiry that those who ignore the Science Court don’t care about the truth. This can give the “Science Court respecters” the confidence to coordinate action without the approval of the “Science Court disrespecters.”

The intellectual integrity of public discourse has declined even more since the 1970s and 1980s when Kantrowitz and Drexler were writing. Perhaps few people still care about “high quality”, impartial, factual investigations of controversial issues.

But by the same token, it’s easier than ever for a new institution to be “conspicuously the best thing around” for those who do care.

I am not anywhere near aligned with Curtis Yarvin politically, but I am intrigued by his proposal for making Twitter the “conspicuously best around” adjudicator of factual questions.

Imagine a sort of Twitter court that had the intellectual firepower and confidence to decide any matter of right and wrong—much as a real-world court can. Was Covid a lab leak? Was Shakespeare Oxford? Did FDR have prior knowledge of Pearl Harbor? Could UFOs be real? Does amyloid cause Alzheimer’s? Is Hunter’s laptop authentic? And so on.

…

The fundamental structure of an online trial is the same as the structure of a regular trial. Lawyers for both sides work together to produce an argument. This argument is presented to a judge or jury, who renders a decision. Online, the details are different but the structure is the same.

…

What would help the neutral judge the most is an argument tree, which makes it easy to look through every argument from either side, see the other side’s rebuttals to each of those arguments, the rebuttals to the rebuttals, and so on—until one side is tired of repeating itself, and refers back to its last point. This kind of collaborative document was unthinkable to the scribes of 13-century Kent, or whatever, but is trivial today.

This is essentially the same idea as Kontrowitz’s — let representatives from disagreeing perspectives debate a controversial question of fact, and let a neutral judge come to a conclusion.

Yarvin adds the “argument tree” feature, which I think is a straightforwardly good idea, and also suggests implementing a prediction market to bet on how the judge will decide, which I’m less sure about.

He also thinks the judges should be “brilliant, open-minded generalists”, which sounds nice but is nowhere near enough of a selection procedure to avoid the “court” becoming laughably biased in whatever direction Twitter’s CEO wants.

At a minimum, I think, anybody you whose participation you value in a Science Court (or Twitter Court, or whatever), anybody whose participation would make the institution better, must believe they have a fair chance to convince the court. You do not want all the scientists to shun your newly created system because they think the court’s sponsor is a dangerous ideologue. So you need some stronger guarantees of neutrality, like “both parties in a dispute must approve the judges/jurors” or “anyone can set up a valid court” or things like that.

But regardless, the idea of a “fact forum” or “science court” or “Twitter court” is a convergent one. The best known way to resolve disputed issues is structured debate.

What we have now is unstructured dispute. Anyone in the US is (mostly) free to express any opinion, but people with different opinions talk past each other. There are no “ground rules”; nobody can be held accountable for goalpost-shifting or making rhetorically effective non sequiturs.

When disputants submit to a formal structure — when they must make their points clear, explicit, precise, and civil; when they must provide pertinent evidence; when they must address counterarguments; when they must swear to tell the truth and face penalties if they do not; when they are accountable before a neutral arbiter — disagreement becomes an engine for producing a better understanding of reality.

In fact, Peter Drucker thought “knowledge workers” are so emotionally invested in their professional ethic and identity — being a “good lawyer” or “good chemist” or whatever — that the rise of educated professionals in the workplace (in the 1970s) was a novel threat to firms. Drucker recommends that knowledge workers need to be carefully sandboxed by generalist managers so that their professional biases don’t dominate the firm’s decisionmaking.

In fact, the professional organization doesn’t need to be a single centralized body at all; you can let anyone host and update the list of members, so long as you have a protocol for resolving disagreements between nodes.

“Oh, I see you have John Smith on your version of the members list. Don’t you know he was expelled for research misconduct?”

“No, I hadn’t heard that, let me see the investigation and check if it’s valid.”

“Ok, looks good, I’ll update my node to include that info.”

Making a version of this protocol that’s robust to “bad” nodes is probably a solved problem out there, but I’m not sufficiently familiar with this field.

I think we discussed a similar concept on twitter a bit ago? IMO it would be really good to create a system like this, and it seems like something that it would be natural for the rationalist community to work on.

Oh boy so I have a bunch of thoughts on this!

1. Professional associations with teeth: So there's an obvious failure state to to be wary of here, which can be seen from the fact that the lawyers' and doctors' guilds already *have* teeth, they just don't use them. Like, from what I gather, they seem to have gotten into a state where, rather than attempting to maintain trust in their professions by expelling wrongdoers, they instead attempt to maintain trust by *not* expelling wrongdoers except in the worst cases, figuring that the way most people tend to think means that each expulsion will contribute to the impression that lawyers (or doctors) in *general* are untrustworthy, rather than that the remaining ones must be trustworthy. This has the obvious consequences.

I do have to wonder if perhaps a factor here is that their teeth are maybe too strong, i.e., you're not allowed to practice at all without being a member. But this seems like a failure mode that could happen regardless, and indeed it seems like we do see essentially the same phenomenon in some academic fields as well, even where there are basically no teeth at all; basically it seems to be pretty common. So the big question is how to avoid it? That's not something I have any answer to, but it really requires an answer.

...is this one of the things that "anyone, even an outsider, can start an investigation" is meant to address? It does seem likely to me that the sticking point is largely *starting* investigations, not biasing the verdicts. (Although I assume the point about the juries is meant to address that, too.) So maybe this would help here.

Of course, letting anyone start an investigation means that -- like with real courts -- you then also need some way to prevent people from abusing that, i.e., some way to have frivolous cases dismissed early. You probably can't fine people for bringing frivolous cases (or can you? if you set it up right maybe you can), but if someone does it repeatedly you can them from bringing more cases, I guess? (In real courts that's rarely done because preventing from someone from suing is, y'know, really bad, but doing it in this more informal setting may not be such a problem.)

Except, some of the abusive uses might come in ways that *aren't* so easily dismissed as frivolous. Thinking about medicine again, there's already a problem of legally-defensive healthcare; doctors aren't really worried so much about losing their license, but they are worried about being sued for malpractice. How do you impose more consequences without making things even more *defensible* rather than more *correct*? This seems troublesome. But I guess you were thinking of this more in the fact context rather than the medical context? I was just thinking of the medical context because it seems there like the AMA is a dysfunctional example of professional-association courts. (With, I guess, the public courts being dysfunctional in the *opposite* direction in this context -- one not strict enough, the other too strict.)

2. Argument trees! (Or graphs.) Argument graphs are so great. They are so underused. To respond to your and Rand's discussion of Wikipedia -- sure, Wikipedia can summarize a controversy, but only to a certain depth before they start pruning it, and they sure don't have argument graphs!

Man, the whole thing where people just ignore or misrepresent their opponents' arguments instead of actually responding to them annoys me a lot. Although, once a position becomes sufficiently common, it can happen that people bothering to actually argue for intelligently largely vanish, leaving it appearing unsupported.

Like I remember being really glad to see you write this essay a while ago: https://srconstantin.wordpress.com/2017/06/27/in-defense-of-individualist-culture/ It's a point that, though it once needed to be argued for, has faded into the background so much that few arguing for it are really sure *how* to, leading to primarily arguments against it getting circulated; and those arguments against it largely ignore the arguments for it, because they're largely not made, while the few arguments made for it address their opponents only weakly because they just haven't really learned the better arguments. It's a real stupid equilibrium.

(...I need to actually write some of those poltical essays I keep talking about, problem is I'm already overloaded for time, writing about politics is unpleasant, and I have a huge math backlog... maybe after March I'll have some time...)

...jumping back to the topic of argument graphs, and getting a controversy properly written down, can I go on a tangential rant here about how people misrepresent Sabine Hossenfelder? There is so much rounding off of what she says to "dark matter is probably wrong and modified gravity is probably right", even though if you read her actualy posts her position is pretty clearly that the orthodox position is probably mostly correct and that her complaint is that the alternative positions are being misrepresented and underexplored compared to their probability, but not that that probability is higher than that of the orthodox position. And the arguments she makes for this seem to be basically ignored and not responded to as far as I've seen! Are they right? It's hard to say when people aren't properly addressing them! Put it all in an argument graph and make this plain, I say. :P (I mean, I would encourage Hossenfelder to be less sensationalist, and sometimes she seems to pretty clearly emphasize the wrong thing, but that's another matter.)

...OK I thought I had more to say on this but I can't remember it. Oh well.