Neutrality

towards a system of the world

I’ve had post-election thoughts percolating, and the sense that I wanted to synthesize something about this moment, but politics per se is not really my beat. This is about as close as I want to come to the topic, and it’s a sidelong thing, but I think the time is right.

It’s time to start thinking again about neutrality.

Neutral institutions, neutral information sources. Things that both seem and are impartial, balanced, incorruptible, universal, legitimate, trustworthy, canonical, foundational.1

We don’t have them. Clearly.

We live in a pluralistic and divided world. Everybody’s got different “reality-tunnels.” Attempts to impose one worldview on everyone fail.

To some extent this is healthy and inevitable; we are all different, we do disagree, and it’s vain to hope that “everyone can get on the same page” like some kind of hive-mind.

On the other hand, lots of things aren’t great: crumbling institutions, culture war eating everything, opportunistic SEO slop taking over the internet, noise overwhelming signal.

There is a pervasive sense of an old system dying, and a sense of potential that a new one might be born. Venkatesh Rao has somewhat inspired me here with his Mandala and Machine essay, though I’m taking a slightly different lens on it.

These days, savvy people tend to accept that the “world” is a roiling chaotic ball of stormclouds, impossible to get a handle on; that all information is intrinsically untrustworthy; that all environments outside a trusted inner circle are adversarial.

This is not a universal human condition.

And it may not be our permanent condition. The future may hold something more like a “foundation” or a “framework” or a “system of the world” that people actually trust and consider legitimate.

I don’t mean that in a utopian, impossible way; I mean it in the limited, realistic, actually-existing way that trust and legitimacy have been present in (recent and distant) past cultures.

Not “Normality”

To a large extent, we still rely on a deep, though crumbling, reserve of unexamined “normality.” Apolitical, basic, running on 90’s-sitcom scripts; you work at your job, then you come home to your friends or family and relax. “You know, normal.” The thing that seems to have broken in the last decade of Weirding.

A lot of people, of course, are nostalgic for normality. Noah Smith is eager to put the 2010s behind us, for instance.

I can see why, but really, unexamined normality is inadequate. It’s what it feels like from the inside to be Keynes’ “slaves of some defunct economist.”

“Why have people picked up such-and-such extreme, radical view all of a sudden?” Well, it’s the Internet and social media, of course; but more specifically, it’s because that view would always have been attractive to some fraction of people, but in decades past they’d never have heard of it.

A lot of people, for instance, only figured out as adults that Communism had been an influential force in U.S. culture through the 20th century. This was basic background knowledge for me, growing up in an academic family, but for other people it seems to be an electric hidden truth.

Of course some percent of people who read Osama bin Laden’s manifesto for the first time are going to find it compelling! Most people had literally never heard a terrorist’s point of view before. Almost anything he could have written would be more persuasive than “he has no point of view, he’s just evil.”

Unexamined normality’s main protection is silence; it persists only because most people have never heard of any alternative to the way things are. Denser communication networks mean that more people will encounter questions like “but why are things this way?” And, because normality runs on silence, it doesn’t have good explicit answers.

To some extent, weirdness is just the inevitable result of the operation of Mind. Everything unexamined, sooner or later, gets questioned, disputed, messed with. To hope to avoid this is to seek to impose stupidity on the world.

But of course, to the extent that normality was functional, people questioning “the way we’ve always done it” makes things dysfunctional. Things once trusted implicitly can break down, gradually and then suddenly.

What is Neutrality Anyway?

A process is neutral towards things when it treats them the same.

To be neutral on a controversial topic is to take no sides on it. There are many ways this can be done:

consider the topic out of bounds for a space: “no politics or religion at the dinner table”

allow anyone to express their opinion, but take no institutional stand; people may take sides, but the platform/newspaper/university/government that defines the space around them does not.

describe the controversy without taking a side on it

potentially take a stand on the controversy, but only when a conclusion emerges from an impartial process that a priori could have come out either way, such as:

randomization

judicial proceedings

scientific experiment

majority vote, prediction market, or other opinion-aggregation mechanisms

The practical reason to seek neutrality is to allow cooperation between people who don’t agree.

For instance, the Dutch Republic, in the late 16th century, was one of the first polities in Europe to enshrine religious freedom into law rather than establishing a state church. Why? Because the Netherlands were a patchwork of counties, divided between Catholics, Calvinists, Arminians, and assorted “spiritualist” sects, trying to unite and win independence from Hapsburg Spain. It was not practicable for one church to win outright and force the others into submission; their only hope was compromise.

Invariably, real-world neutrality is neutral between some things, not all things. The relevant range of things to be neutral about is determined by:

whom do you want to cooperate with? for what purpose?

what range of opinions and worldviews could they and you hold?

where do differences in views threaten to break down cooperation?

what are the minimal conditions for cooperation to hold?

We don’t care about being “neutral” between literally all strings of characters, or between Earthlings and hypothetical extraterrestrials. We care about neutrality between actually-existing, or plausibly-potential, crucial differences in point of view between potential allies.

Neutrality-producing procedures can expand options for cooperation. Perhaps Alice and Bob can’t cooperate if there’s a risk their disagreement will blow up unexpectedly, but they can cooperate if they can agree to put it aside or submit to a neutral adjudication procedure. The procedure is a “box” they can safely put their conflict in.

Seen from that point of view, the most important property of the “box” is that Alice and Bob have to be willing to put their conflict in it. If either suspects that the “box” is rigged to give the other one the upper hand, it won’t work. The perception of neutrality is the critical element. But in the long run, you earn trust by being worthy of it.

“Neutrality is Impossible” is Technically True But Misses The Point

I once saw a computer science professor respond to the allegation that “neutrality is impossible” by asking “ok, how is my algorithms and data structures class non-neutral?”

So, ok, imagine a standard undergraduate computer science class on algorithms and data structures. It covers the usual material; none of the ideas are controversial within computer science; political discussion never comes up in the classroom because it’s irrelevant to the course.

But yeah, actually, it’s not perfectly neutral.

There’s a technical sense that nobody really cares about, where it’s “non-neutral” to make utterances in a language instead of random strings of sounds, or to use concepts that seem “natural” to humans instead of weird philosophers’ constructs like bleen and grue.

More relevantly, it’s possible for actual people to have objections to things about our “neutral” CS class.

Some people object to the structure of universities and courses themselves; grading, lectures, problem sets, and tests; conflating purposes like credentialing, coming-of-age experiences, vocational training, and liberal-arts education into single institutions called “colleges”; etc.

Some people object to the choices of what goes into a “standard” CS curriculum. Are these the right things to prioritize? Are these concepts valid? Sure, by stipulation nothing being taught is controversial within computer science, but if you ask a mathematician you might get some gripes. Ask a philosopher? A religious mystic? They might say the whole business is rotten and deluded.

Some people object to “apolitical” spaces in themselves. To declare some topics to be “politics” and thus temporarily off limits is to implicitly believe something about them: namely, that they can be put aside for the space of a class, that it is not so urgently necessary to disrupt the status quo that things can’t be left locally “apolitical” while something else gets done.

Even our hypothetical bog-standard CS class takes a stand on some things — it “believes” that certain things are worth teaching, in a certain way. And it’s not just conceivably but realistically possible for there to be disagreement about that!

When we talk about neutrality we have to talk about neutral relative to what and neutral in what sense.

The class is neutral on a wide range of controversial topics, in the sense that it doesn’t engage with them at all. This means that a pretty wide range of people can take the class and learn algorithms and data structures. The range isn’t literally infinite — non-English-speakers, people not enrolled in the college, maybe deaf students if there’s no accommodation, etc, will not be able to take the class.

The question isn’t “is it neutral or not”, the question is, “is the type and degree of neutrality doing the job we want it to do?” And then it’s possible to get into the real disagreements, about what different people are trying to accomplish in the first place with the “neutrality”.

Systems of the World

A system-of-the-world is the dual of neutrality; it’s the stuff that a space is not neutral about. The stuff that’s considered foundational, basic, “just true”, common-knowledge. The framework on which you hang a variety of possible options.

The framework, the system, the “container” of the space, is deliberately neutral between various options, but it cannot be neutral with regards to itself. There has to be a “bottom” somewhere.

Intellectual worldviews “bottom out” in philosophical axioms or concepts. They seem obvious, they may rarely be discussed, but you would have to stop doing your day-to-day work if you truly rejected the foundations on which it rests.2

The literal “world” “view” of viewing Planet Earth as a globe, and all points on the earth as locations on a sphere or its map projections, is itself a framework or system. It is neutral between points on Earth — the globe is global, it picks no sides between countries or continents.3 But it’s still a particular choice. It shows the world as if from a spaceship4 outside, rather than from the point of view of a creature walking around on it.

I’ve been rereading Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle lately, which is about the origins of the broader “system of the world” which includes the Newtonian/Leibnizian views of mathematics and physics, the emergence of political liberalism, the Bank of England and the first financial institutions, the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, etc. Modernity, in other words.

Modernity is a system that aims at a sort of universality and neutrality. But it isn’t the only system that has had such aims. And Modernity absolutely does take certain stands, with which other worldviews disagree.

A “system of the world” is really not the same thing as unexamined normality.

Yes, when living within a system-of-the-world, people trust that system. They rely on it, believe in it, not ironically or provisionally but for real. They treat it as common knowledge that can be assumed in communication. They see the system as true and real, or at least validly reflective of reality, not as a mere hypothesis or lens.

And, yes, people’s faith in systems-of-the-world can shatter when they first learn about something that doesn’t fit.

But strong systems-of-the-world are articulable. They can defend themselves. They can reflect on themselves. They can (and should) shatter in response to incompatible evidence, but they don’t sputter and shrug when a child first asks “why”.

Not every point of view is even trying to be a system-of-the-world. It’s possible to be fundamentally particularist, speaking only “for” yourself, or your community, or a particular priority. Not even aspiring to any kind of universalism or neutrality.

Remember, neutrality is a thing we do sometimes, when we need to. It might be better to speak of “impartializing tactics”, rather than a static Nirvana-like state of “neutrality”. We use “impartializing tactics” in order to broaden our reach: cooperation between people, and also generalization across contexts and coordination across time. In using such a tactic, an entity decides not to care about the object-level stuff it’s being “impartial” about. It “withdraws” to be above the fray in one domain, to gain greater scope and range elsewhere.5

Some entities (people, institutions, cultural viewpoints, etc) don’t choose to withdraw or “rise above” or use these “impartializing tactics” very much at all; they aren’t even aiming to be systems of the world.

We can tell these apart, the same way we can tell apart universalizing religions (like Christianity and Islam, which hope that one day everyone will accept their truth) from non-universalizing religions (like Hinduism; from what I’m told it’s impossible to “convert to Hinduism.”)

“Red tribe” and “blue tribe” memeplexes are non-universalizing. They don’t actually want to be fully general and create a system that “everyone” can live with; they want to win, sure, but not to “go meta” or “transcend-and-include.”6

Let’s Talk About Online

Right now, in the parts of the world I can see, I think our system-of-the-world is extremely weak. There are very few baseline “common-sense” assumptions that can be treated as common knowledge even among educated people meeting on friendly terms. What we learned in school? What we saw on TV? Common life experiences? There’s just a lot less of that than there once was.

The literal UI affordances of software apps are, I suspect, an embarrassingly large amount of our current “system-of-the-world”, and while I generally want to stick up for software and the internet and “tech” against its enemies, the tech industry was certainly never prepared for the awesome responsibility of becoming The World!

I think it’s ultimately going to be necessary to build a new system to replace the old.

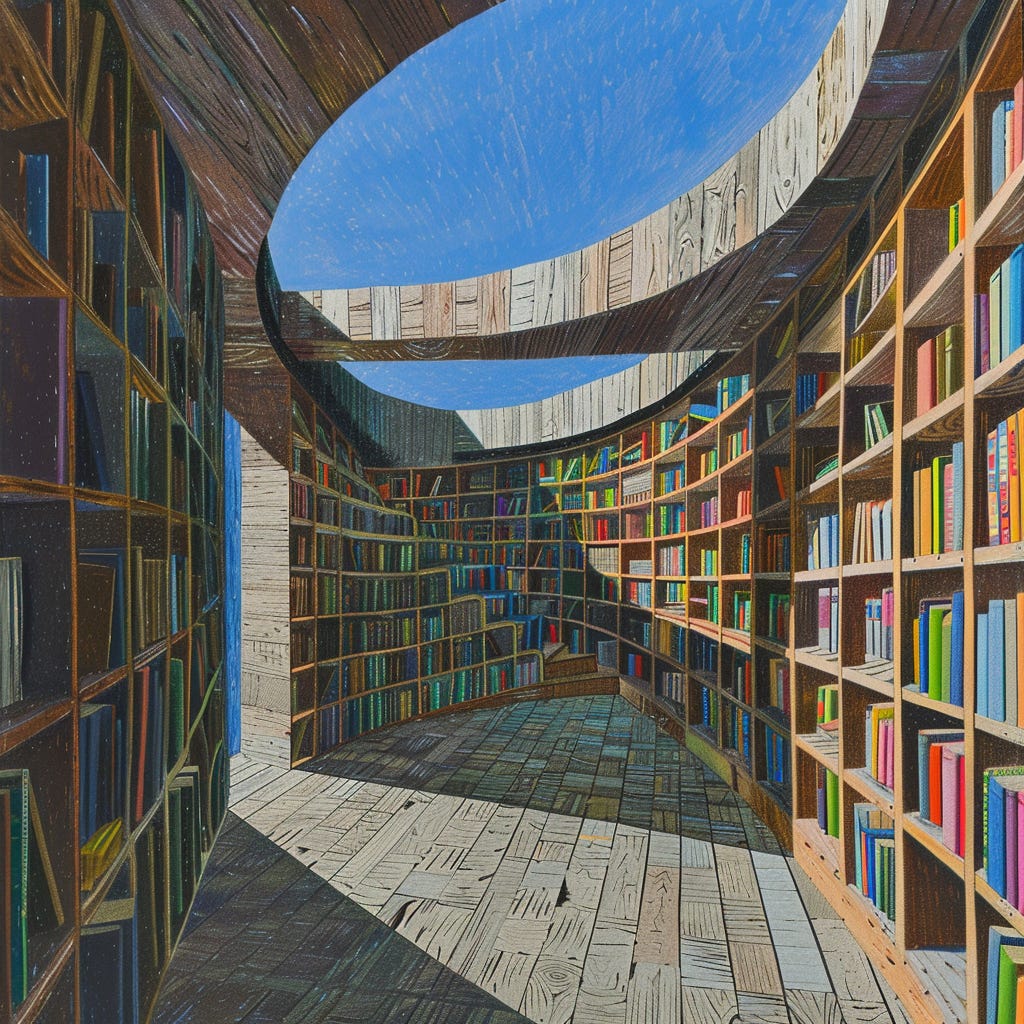

In a narrow sense that looks like an information system. What replaces Google, Wikipedia, blogs, and social media, in the way that those (partially) replaced traditional media, libraries, schools, etc?

In a deeper sense, our present day’s conflicting viewpoints “live in” a World defined by the tools and platforms that host them.

There are also social, political, economic, and natural processes in the physical world; we don’t live in cyberspace, we need to eat, and physical-world factors and forces constrain us; but there’s no shared conceptual framework, no “World”, that encompasses all of them. There’s just Reality, which can bite you. The closest thing we’ve got to a universal conceptual World is your computer screen, I’m sorry to say.

And it just isn’t prepared to do the job of being, y’know, good.

In the sense that a library staffed by idealistic librarians is trying to be good, trying to not take sides and serve all people without preaching or bossing or censoring, but is also sort of trying to be a role model for children and a good starting point for anyone’s education and a window into the “higher” things humanity is capable of.

The “ideal library” is not a parochial or dogmatic ideal. It’s quite neutral and understated. As a library patron, you are in the driver’s seat, using the library according to its affordances. The library doesn’t really have a loud “voice” of its own, it isn’t “telling” you anything — it’s primarily the books that tell you things. But the library is quietly setting a frame, setting a default, making choices.

So is every institutional container.

And most institutions and information-technology frameworks are not really ambitious enough to be setting the “frame” or “context” for the whole World.

They make openly parochial/biased decisions to choose sides on issues that are obviously still active controversies.

Or, they use “impartializing tactics” chosen in the early-Web-2.0 days when people were more naive and utopian, like “allow everyone to trivially make a user account, give all user accounts initially identical affordances, prioritize user-upvoted content.”

These techniques are at least attempts at neutral universality, and they have real strengths — we don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater — but they weren’t designed to be ultra-robust to exploitation, or to make serious attempts to assess properties like truth, accuracy, coherence, usefulness, justice.

“But an algorithm can’t possibly assess those properties! That’s naive High Modernist wishful thinking!”

“Well, have you tried lately? Are you sure nothing we’re capable of now — with LLMs, zero-knowledge proofs, formal verification, prediction markets, and the like — can make a better stab at these supposedly-subjective virtues than “one guy’s opinion” or “a committee’s report” or “upvotes”?”

The alternative viewpoint is “there is no substitute for good human judgment; we don’t need systems, we need the right people to talk amongst themselves and make good decisions.”

To that, I say, first of all, that the “right” people to handle issues around information/truth, trust/legitimacy, and dispute resolution are more likely to congregate around attempts to build neutral, technical, robustly unexploitable systems. The ideal archetype of “good human judgment” is a judge…and judges are learned in law, which is a system. (Or protocol, if you prefer.)

Second of all, it is not enough for the “right people to talk amongst themselves”. There are some very brilliant people who only reveal their insights in private group chats and face-to-face relationships. They don’t all find each other. And the scale of their ambitions is limited by the scale of recruitment and management that this “personal judgment” method can manage. And I shouldn’t have to explain why “just put the right people in charge of everything” is unstable.7

But sure, I generally do concede that a lot of human judgment is irreducible. It’s just not everything, and human judgment can be greatly extended by protocols. There may be no technological substitute for good people, but there are certainly complements.

I may write some more specific ideas for how this could shape up in a later post, but really I’m in the earliest stages of speculation and other people know much more about the object level. What I want to encourage, and seek out, is a healthy vainglory. You actually can contemplate creating a new (cognitive) foundation for the world, something that vast numbers of very different people will actually want to count on. It’s been done before. It doesn’t require anything literally impossible. It’s not wilder than stuff respectable people discuss freely like “building AGI” or “creating a new and better culture”.

In fact, what makes it seem crazier is the concreteness; it’s a happily-ever-after endgame (even though it doesn’t need to be anywhere near literally eternal or perfect) that’s supposed to be made of mundane moving parts like procedures, UI elements, and algorithms — ideas that never seem that great when specifics are proposed. But I think the possibility of “dumb proposed ideas that won’t work” is a strength, not a weakness; the alternative is to speak concretely only about relatively narrow things, and vaguely about Utopia, and leave the vulnerable space in between safely unspoken (and thus never traversed.)

So yeah. Broken, crooked ladders towards Utopia are a good thing, actually. Please, make more of them!

Yes, yes, David Chapman thinks this is false, that there are no valid axioms or foundations anywhere and we can still do our “jobs” while recognizing that all frameworks are provisional and groundless. I have, in fact, thought about this, and I’ll get to that in a minute.

well, except via the convention of putting the North Pole on top; “Why are we changing maps?”

or angel; in Paradise Lost there’s a surprising amount of astronomy, and a lot of attention lavished on what Satan sees as he approaches Earth from the outside.

Venkat Rao thinks of “mandalas” as caring about people and “machines” as driven by knowing, not caring. I think this is a screwy dualism; knowing and caring are inextricably linked. The “thinking vs. feeling” dichotomy has always been fake. I expect this is because he is personally a “thinker” whose feelings aren’t super strong, so it seems natural to him to divide the world into “thinkers” and “feelers”, whereas I can never decide which kind I am. (Mercury/Moon conjunct, lol.)

But there is a real thing I see about “distance” and “withdrawal” when you go up a meta level. The more meta you go, the less involved with the object level you can be; you can “touch” many more things, but more lightly and vaguely. “Caring” is conserved.

Ken Wilber’s phrase.

I shouldn’t, but I do. #1: Not everybody agrees on who “the right people” are; if you tell me you’ll just put “the right people” in charge, I might not trust you. #2: The “right people” may not continue to make the “right” decisions when given more power or resources. #3: what about succession? can the “right people” choose other “right people” reliably? if they could, wouldn’t they be doing it already? The world doesn’t look like wisdom and knowledge is stably being transmitted within a network of elite dynasties.

On the question of whether a data structures and algorithms class is neutral - it just clearly isn't "neutral", when you only have 15 weeks (or 10 weeks at a quarter system university) and can't teach *every* data structure and algorithm that people talk about. I would bet there's actually a lot of internal debate in computer science faculties these days about whether maybe the curriculum of that class should be revised to include a week about neural nets and backpropagation, or whether that is better to hold off to another class! There were hard-won debates decades ago that got NP-hardness included, but not every topic that someone thought was interesting.

Also many of the points you were making in the second half were closely related to a paper I was reading earlier this afternoon: https://philarchive.org/rec/NGUTIS

Nguyen points out that we need expert judgment to make the best decisions we can; but experts are people too and sometimes make decisions on behalf of their own interests rather than ours; so we ask for transparency, where experts explain their judgments; but we can't properly understand expert's explanations of their judgments. When we ask for transparency, we inevitably either require experts to falsify the explanation for their judgment, or to limit their judgments to ones that can be justified to non-experts, and either way there is a serious loss.

He doesn't take this next step, but replacing experts with protocols doesn't get us out of the problem - this is precisely the problem of explainable AI: our best neural nets for classifying things are often unexplainable; but these best neural nets are often biased in some way (not necessarily based on their *interests*, perhaps just based on biases in their training data); so we ask for explainability; but insisting that they only use explainable methods limits the methods we have access to.

Speaking of Paradise Lost: I just read an article on Milton's cosmology. Milton was agnostic about geo vs heliocentrism, but he was a friend of Galileo, and committed to Baconian science. In the epic Galileo and his telescope are the only contemporary objects ever listed or referenced.

The angel Rafael tells Adam that the answer to this riddle requires minding to what you can understand first. Adam responds, "Well hast thou taught the way that might direct / Our knowledge, and the scale of nature set / From centre to circumference, whereon / In contemplation of created things / By steps we may ascend to God".

This attitude is meant to convey that we will figure it out eventually, even if not yet.

It must have been agonizing for that century when the outcome of the debate was uncertain. But the creation of neutral ground for having it made more discoveries possible.